Bonus Scene: “A Singular Girl”

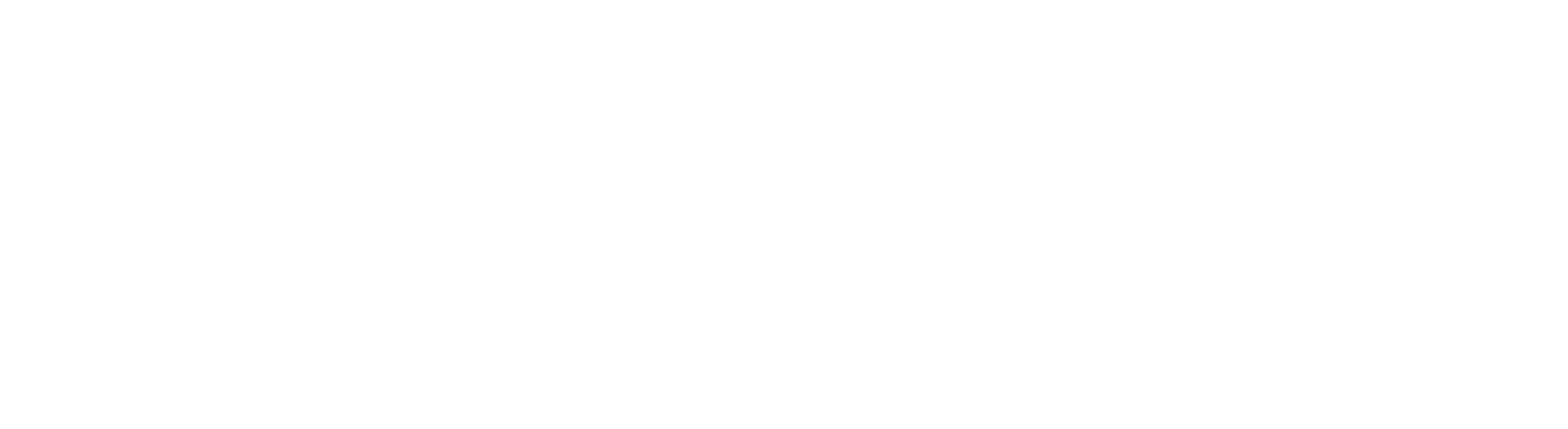

When I first finished writing The Duke, it included scenes in which Amarantha and Gabriel weren’t together. There are still a few of those in the published novel: they travel great distances to find each other, after all. But to reunite them as speedily as possible after their separation — while remaining true to their appearances in The Rogue and The Earl — I ended up cutting some scenes of Amarantha searching for Gabriel across Scotland.

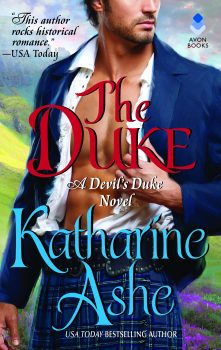

One of those scenes takes place when Amarantha has just reached Scotland, and she happens upon young Miss Elizabeth Shaw. First seen in The Rogue and then later in The Duke, utterly unconventional Libby Shaw gets her own love story in The Prince.

“I disapprove, Mrs. Garland.”

“Dear, kind, good Mr. Hay.” Amarantha buttoned the cloak to her chin. “Each time I leave this building you disapprove. If you had your wish, I would climb into that traveling trunk and never leave it. You would bring me tea and bread with butter—if we could afford butter—and read me sea stories to lull me into believing we had never set foot on land.”

The lines that fanned from the corners of his eyes deepened. Carved into his skin by a life spent working iron in shipyards, they were lines of kindness.

“Your father would disapprove, too,” he said.

The longtime loyalty of the soldier to his commander was occasionally inconvenient.

“My father has never disapproved of anything I have ever done. He has been outrageously indulgent.” To unfortunate excess. She tucked a small notebook and a pencil into her satchel. “And do remember to call me Anne when we are alone. It will then become habit for you to do so when others are nearby.”

He lifted a hand twisted with arthritis and pinched the bridge of his nose. She saw his grimace and suspected the gesture was to hide a flare of pain.

She crossed the tiny room adorned only with two plain chairs and a table before the stove, and his sleeping matt now rolled up in the corner. He insisted that she sleep on the cot in the adjoining chamber with her traveling chest. Combined, they could afford no better quarters. But she wanted no grander residence. It would not suit her program in Leith.

“Corporal Hay, I am not—”

“If you won’t call me Nathaniel, I’ll not call you Anne.”

“Nathaniel, will you renege now on your vow to assist me?”

“You’re the daughter of a wealthy earl.”

“I am the widow of a poor missionary.”

“You wouldn’t need my assistance if you called upon your father, or your husband’s family, for help.”

“I cannot. They would not understand.”

Emily would. But Amarantha had not yet posted the letter she had written to her elder sister as they had come into port. She needn’t even have written it to arrange a homecoming. One of Emily’s closest companions in London, Lady Constance Read, now lived a stone’s throw from Edinburgh. Constance would give her warm welcome if she sought it now.

She did not seek it. She could not. Too much had happened since she had left her parents’ home. Too much had changed.

She had changed.

Her family would ask questions, many questions that she could not answer satisfactorily. But she could not lie to them. Never again.

Now she wanted only to discover where Penny had gone in Scotland and to help her if she could. Given the refusal of Paul’s family to acknowledge Penny’s blood relationship, Amarantha doubted that money and noble connections could aid in finding her friend anyway.

“My lady—”

“Anne.”

“See reason. This skulking about troubles me.”

“If you wish to leave, Nathaniel, you should. The landlord will not ask for the rent again until next month. By then I will surely have found trace of Penny and be long gone from here. I will live comfortably on the money I can take in by sewing. I have already made friends with the laundry women at the end of the block, who will send work my way.”

“A girl like you shouldn’t be working.”

“Fortunately I am not a girl. I am a matron and a widow who until seven months ago shared the care of an entire congregation with my husband and until three months ago did so alone. If you leave now, Nathaniel, I will be well.”

“I’d as soon leave one of the colonel’s daughters to fend for herself in a strange town than I’d have welcomed a French bayonet between my ribs at Yorktown.”

“Then do cease pecking at me.” Reaching for the satchel, she buckled the clasp and slung the bag over her shoulder. “And do rest, if you can resist going into the smith’s shop and offering help.”

“Once a smithy, always a smithy.”

She glanced at the stump of his left arm and allowed one of her brows to rise. “And you think me unreasonable. Hm.”

Pale eyes twinkled in his weathered face.

“On my walk to the pub,” she said, moving to the doorway, “I will stop into the apothecary shop and—”

“You’ll not be spending your last pennies on poppy syrup for me.”

“Not for you. For the headache that your badgering will most certainly cause me before week’s end.”

With a fond smile, she entered the alleyway and walked to its end. The first shop on the street was the apothecary, and she approached the chemist’s counter. While she waited for him to see to the needs of a portly gentleman in collar points up to his nostrils, she stood silently.

When a woman in a pleated gown of the most gorgeous shade of watermelon came into the shop and moved in front of her, Amarantha made no complaint. Dressed inexpensively, she could not command the attention of a shopkeeper in the manner that an earl’s daughter could. But the less notice others took of her, the easier it would be to continue to slip in and out of sailors’ pubs and tradesmen’s hostels in her search for Penny.

Anonymity now was comfortable. Cleansing. It suited her.

When finally the apothecary finished with other customers, she asked the price of a small bottle of laudanum.

“What’ll you be wantin’ it for, lass?”

A sennight spent in Scotland already, yet that word—lass—the name that only one man ever had called her—still felt like a hard pinch to the back of her neck.

“My uncle”–uncle seemed a more respectable relationship than my father’s former soldier with whom I am temporarily allied–“suffers from aches in his joints. It is to allow him to sleep at night.”

“You don’t want opium for that,” said a girl who was studying a display of throat lozenges. With golden curls, fair skin, and brilliantly blue eyes, she was not yet a woman and simply but neatly garbed.

“I don’t?”

“What’ll she be wantin’, Miss Shaw?” the apothecary said, peering at the girl over his magnifying lenses.

“Ginger, of course,” she said as though addressing the lozenges. “It does not muddle the brain as laudanum does, and it has the positive effect of calming the stomach as well. And turmeric if any can be had. Do you have any turmeric, Mr. Glenn?”

“Aye, miss,” he said, a brow arcing. “You’ve bade me stock it afore.”

Now her head bobbed up. “Indeed I have, excellent Mr. Glenn!” She looked at Amarantha. “Both ginger and turmeric will decrease the inflammation of your uncle’s joints without adverse effects. If he does not wish to swallow them with water, mix them into tea or food. They are both tasty.”

“I see. Thank you.” Amarantha turned to the apothecary. “If you please, sir.”

“You are English,” Miss Shaw stated.

“I am.” Amarantha exchanged coins for the powders.

“Your voice does not suit your clothing. One is cultivated; the other is not. And your skin is tanned, as though you have spent time on a ship recently, but you have few profound wrinkles so you have not spent a lifetime beneath the harsh sun. Have you recently disembarked?”

“I have.” She smiled. “I daresay half the people in any port town have.”

The girl’s eyes widened. “I daresay you are correct. I do not live in Leith,” she added, a crease darting up the bridge of her nose. “Not yet, at least. My father and I have come here today to look for a house to hire. We have been living at our friend’s house in Edinburgh, but she is to marry and so we must find other lodgings, and Leith is less expensive than Edinburgh. We visit our friends in Leith quite a lot, but I had not really considered what a change it will be to reside here. Society in Edinburgh is very static, you see, except at the university and the occasional duke who comes and goes rather at random, and inconveniently as it happens, when one wants to study his collection of human skulls, you see.”

Human skulls? What a singular girl.

Amarantha smiled. “I suspect that would be inconvenient, it’s true.”

“Remarkably so,” Miss Shaw replied. “But I suppose that must be the way of it with dukes. For even though the duke in question is wonderfully generous, he is not at all stationary, as one might expect such a man to be, given all the long hours he must sit around in Lords and at court and what have you.”

“Hm. Perhaps.” But Amarantha had learned long ago that it was deeply unwise to trust in what one expected of a man, rather in the opposite.